Clinicians’ Perspective on the Global Momentum and Local Readiness on Phage Therapy

A look at recent clinician surveys

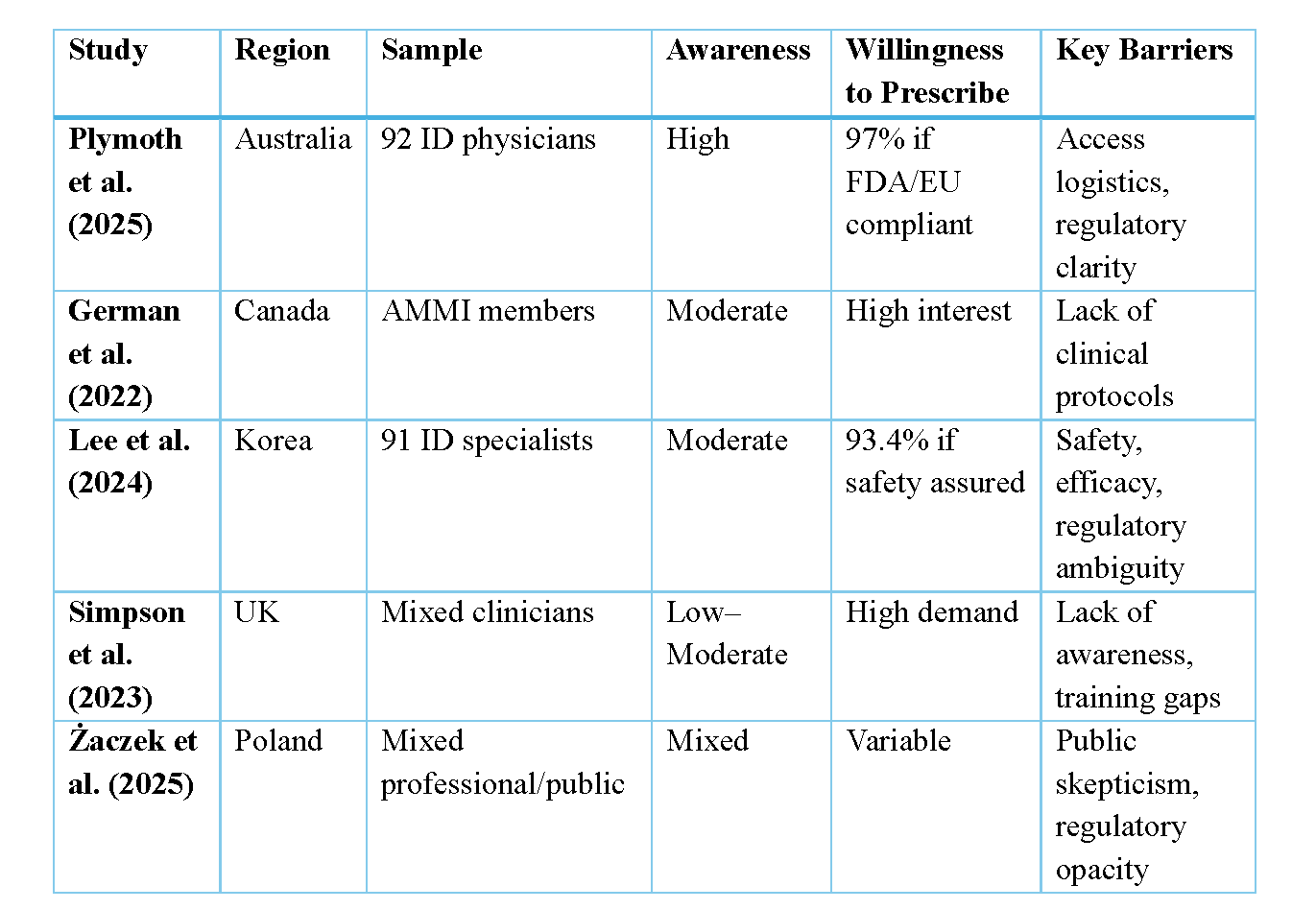

Between 2021 and 2023, clinician attitudes toward phage therapy were explored in country-specific surveys from Australia, Canada, Korea, Poland, and the United Kingdom [1–5]. The largest survey to date was conducted in Poland with over 1,000 participants.

Consistently, these surveys found that clinicians are aware, interested and cautiously optimistic about phage therapy. Many clinicians surveyed from these five countries have general awareness of phage therapy, particularly as an adjunct or alternative to antibiotics. In both the Australian and Korean surveys, most respondents rated themselves as having an intermediate level of knowledge. In Australia, over 80% of infectious diseases physicians expressed interest in prescribing phages, especially for multidrug resistant infections. The UK survey found just over half of participants reported a high level of awareness, viewing phages as a viable adjunct or alternative to last-line antibiotics. Canadian and Korean specialists reported similar enthusiasm, citing unmet clinical needs and the potential for personalised microbiological targeting. Even in Poland, where phage therapy has historical roots, clinicians are calling for clearer regulatory pathways and broader clinical access.

Several surveys also explored key clinical priorities for phage therapy development. Canadian clinicians identified respiratory, bone and joint, and endovascular infections as high-priority indications. Similarly, Korean and Australian respondents prioritised bone and joint infections, as well as cystic fibrosis-related lung infections, and prosthetic device infections. Target pathogens were largely consistent amongst the different surveys, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, non-tuberculous mycobacteria, and Enterobacterales (including ESBL and carbapenemase-producing strains) frequently mentioned. An interesting nuance emerged from the UK survey, which included participants from a broader range of medical and surgical specialties. Their findings suggested that bacterial priorities vary by specialty. For example, orthopedic surgeons and dermatologists prioritised Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, while respirologists highlighted Mycobacterium, Pseudomonas, and Burkholderia.

In addition to clinical priorities, many surveys explored the barriers to delivering phage therapy. Australian respondents pointed to issues around timely access, logistics, and efficacy. In Korea, well-informed clinicians expressed similar concerns, particularly regarding efficacy, access, regulatory processes, and safety. Among Korean respondents less familiar with phage therapy, safety was the primary concern. In Poland, those who felt well-informed were less likely to view safety as a major issue. While the UK survey did not specifically ask about barriers, a small number of participants expressed a desire for more information.

Together, these surveys offer valuable insights into how clinicians across different regions and specialties view phage therapy. However, the field is evolving rapidly and so are clinical attitudes, perceived barriers, and opportunities. To better understand the current landscape, we developed and distributed an international survey aimed at capturing clinician perspectives and real-world experience with phage therapy [6].

Our 23-question survey was divided into three sections: respondent demographics, attitudes toward phage therapy, and experiences with phage therapy. It was distributed from October 15, 2024, to January 30, 2025, to members of the Global Clinical Phage Rounds — a network of more than 300 clinicians, health professionals, and scientists involved in phage therapy.

We received responses from 30 clinicians across North America, Europe, Oceania, Africa, and Asia. Most (26) were infectious diseases and/or microbiology (clinical or medical) trainees or specialists. The remaining respondents included two clinicians from other specialties, a reference laboratory service manager, and a pharmacist. Of these, 20 respondents reported current or previous experience with phage therapy so were invited to complete the third section of the survey. They represented a range of roles, including medical and clinical microbiologists, infectious diseases physicians (some working in transplant medicine), and a pharmacist. In the third section, all the previously mentioned continents were represented, except Africa.

Key Findings

Knowledge and Priority Areas

Most respondents considered themselves well informed about phage therapy, with over 85% rating their knowledge as “well” or “very well” informed compared to their peers. These results are notably higher than in earlier surveys — possibly reflecting a sampling bias, as respondents were part of a phage therapy interest group. Nearly all (93%) of our respondents said they would consider enrolling their patients in a phage therapy clinical trial.

When asked about target pathogens, the highest-ranked organisms were Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella species, and Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA). The top clinical indications were bone and joint infections, respiratory tract infections, and urinary tract infections. While the first two align with past surveys, the addition of urinary tract infections reflects a newer area of interest. Recent clinical trials targeting these syndromes include diSArm (S. aureus bacteremia), ELIMINATE (E. coli UTI), and BX211 BiomX (P. aeruginosa and cystic fibrosis) trials [7-9]. As of August 2025, over 60 clinical trials involving phages are registered on ClinicalTrials.gov — highlighting rapid global progress.

Clinical Use

Among respondents with phage therapy experience, 71% had treated between 1–10 patients, while 29% had treated more than 11. Clinicians reporting higher patient volumes were based in Europe, Oceania, and Asia. Phage therapy was most delivered through single-use cases such as compassionate use, special access schemes, or named-patient programs. Clinical trials were reported in Oceania (phases I–III) and Europe (phases I–II), with one European respondent also noting experience with magistral compounding. Phages were sourced from a range of facilities, including academic centres, international collaborators, industry partners, phage banks, and in-house laboratories. Delivery methods included intravenous (most common), followed by topical, inhalation, instilled (e.g., bladder or joint), and oral routes.

Barriers and Concerns

The most frequently cited concerns around phage therapy were access to phages (26%), regulatory guidance (20%), and clinical evidence (18%). When asked to select their single biggest concern, clinical evidence (35%) and regulatory guidance (28%) topped the list — consistent with findings from previous country-specific surveys. Encouragingly, the clinical evidence base is growing, with an increasing number of trials now in development or published. On the regulatory front, our group recently published results from a global survey of phage therapy regulators, highlighting key steps needed to improve clinical access, including raising awareness, fostering engagement, and strengthening collaboration across regulatory bodies [10].

Among experienced clinicians, funding emerged as the top barrier to phage therapy (27%), followed closely by access to phages and pharmacy support. Financial constraints remain a global issue. Since naturally occurring phages cannot be patented, industry investment may be limited. Addressing both regulatory frameworks and funding models will be essential for sustainable clinical integration.

Final Thoughts

Clinicians have an important role to play in the future of phage therapy from identifying suitable patients to contributing to research, data sharing, and regulatory discussions. Respondents to this survey highlighted the ongoing need to strengthen clinical evidence, clarify regulatory pathways, and improve access to phage products. As the field continues to grow, clinician engagement will be essential to translating phage therapy from promising cases to routine care and ultimately, improving outcomes for patients facing difficult-to-treat infections. The surveys also highlighted regulatory fragmentation which persist globally with limited harmonisation and inconsistent GMP expectations. Overall, prescriber enthusiasm is high, especially in the context of antimicrobial resistance, but regulatory ambiguity and access logistics remain key barriers.

Comparative Matrix of surveys on clinicians’ perception towards phage therapy

References

1. Plymoth M, Lynch SA, Khatami A, et al. Attitudes to phage therapy among Australian infectious diseases physicians. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2025; 66:107579.

2. German GJ, Kus JV, Schwartz KL, Webster D, Yamamura DL. P73 Experience and interest in bacteriophage therapy in Canada: an AMMI Canada survey. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can 2022; 7.

3. Lee S, Lynch S, Lin RCY, Myung H, Iredell JR. Phage therapy in Korea: a prescribers’ survey of attitudes amongst Korean infectious diseases specialists towards phage therapy. Infect Chemother 2024; 56:57.

4. Simpson EA, Stacey HJ, Langley RJ, Jones JD. Phage therapy: awareness and demand among clinicians in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2023; 18:e0294190.

5. Żaczek M, Zieliński MW, Górski A, Weber-Dąbrowska B, Międzybrodzki R. Perception of phage therapy and research across selected professional and social groups in Poland. Front Public Health 2025; 13:1490737.

6. Alvarez RD, Finlayson-Trick ECL, Lin RCY, German GJ. Phage therapy: An international survey of attitudes and experiences amongst clinicians. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2025, 107627, ISSN 0924-8579, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2025.107627.

7. Armata Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Study evaluating safety, tolerability, and efficacy of Intravenous AP-SA02 in subjects with S. Aureus bacteremia (diSArm). 2024. Available at: ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT05184764. Accessed 19 March 2025.

8. Locus Clinical Operations. A Study of LBP-EC01 in the treatment of acute uncomplicated UTI caused by drug resistant E. Coli (ELIMINATE Trial). 2025. Available at: ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT05488340. Accessed 19 March 2025.

9. BiomX, Inc. Nebulized bacteriophage therapy in cystic fibrosis patients with chronic Pseudomonas Aeruginosa pulmonary infection. 2023. Available at: ClinicalTrials.gov registration number: NCT05010577. Accessed 19 March 2025.

10. Alvarez RD, Årdal C, Classen AY, Nagel TE, Ceyssens P-J, German GJ. Cross-border dialogue: An international survey of regulators on phage therapy. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2025; :107614.